European Starling

| Common Starling | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Adult S. v. vulgaris in England | |

| Conservation status | |

|

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1) |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Sturnidae |

| Genus: | Sturnus |

| Species: | S. vulgaris |

| Binomial name | |

| Sturnus vulgaris Linnaeus, 1758 |

|

|

|

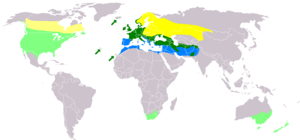

| Native: yellow, breeding summer visitor; dark green, resident breeding; blue, wintering. Introduced: light yellow, breeding summer visitor; light green, resident breeding. |

|

The European Starling, Common Starling or just Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) is a passerine bird in the family Sturnidae.

This species of starling is native to most of temperate Europe and western Asia. It is resident in southern and western Europe and southwestern Asia, while northeastern populations migrate south and west in winter to these regions, and also further south to areas where it does not breed in Iberia and north Africa. It has also been introduced to Australia, New Zealand, North America, and South Africa.

Contents |

Taxonomy

In the genus Sturnus, the European Starling is the type species, the one with all the typical characteristics of its genus. It is in this genus that the terrestrial feeding technique of open-bill probing is most advanced; the technique involves prying into the ground by inserting and opening the bill as a way of searching for hidden food items. European Starlings have the physical traits that enable them to use this feeding technique, which has undoubtedly helped the species spread far and wide.[1]

Along with Sturnus vulgaris, the Sturnus genus includes a number of species which are apparently more-or-less distantly related, but some contend that if the taxonomy is to be based on natural evolutionary grouping, then only the European and Spotless Starling ought to be grouped together.[2]

Subspecies

There are several subspecies of the European Starling, which vary in the iridescence of adult plumage. With gradual variation over geographic range and extensive intergradation, the subspecies are said to be clinal. Acceptance of different subspecies varies between different authorities.[3][4][5][6]

- Sturnus vulgaris vulgaris Linnaeus, 1758. Common Starling. Most of Europe, except the far northwest and far southeast; also Iceland and the Canary Islands, where it is a recent colonist. Introduced populations worldwide also belong to this subspecies.

- Nominate subspecies. The gloss is green on the head, belly and lower back, bronzy purple on the neck to upper chest and back, and purplish on the flanks and upper wing-coverts. Inconspicuous light buff fringes are present on the under wing-coverts. In eastern parts of range, more purplish and less bronzy gloss.

- Sturnus vulgaris faroensis Feilden, 1872. Faroese Starling; sometimes misspelt faeroensis or faroeensis. Faroe Islands.

- Slightly larger than nominate, especially bill and feet. Adult with darker and duller green gloss and far less spotting even in fresh plumage. Juvenile sooty black with whitish chin and areas on belly; throat spotted black.

- Sturnus vulgaris zetlandicus Hartert, 1918. Shetland Starling. Shetland Islands.

- Like faroensis but intermediate in size between that and vulgaris. Birds from Fair Isle, St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides are intermediate between this subspecies and the nominate and placement with vulgarisor zetlandicus varies according to authority. Dark juveniles are occasionally found in Scotland and southwards, indicating some gene flow from faroensis or an original polymorphism that became dominant in faroensis.

- Sturnus vulgaris granti Hartert, 1903. Azores Starling. Azores.

- Like nominate, but smaller, especially feet. Often strong purple gloss on upperparts.

- Sturnus vulgaris poltaratskyi (Finsch, 1878). Eastern Bashkortostan eastwards through Urals and central Siberia, to Lake Baykal and western Mongolia.

- Like nominate, but gloss on head predominantly purple, on back green, on flanks usually purplish-blue, on upper wing-coverts bluish-green. In flight, conspicuous light cinnamon-buff fringes to under wing-coverts and axillaries; these areas may appear very pale in fresh plumage.

- Sturnus vulgaris tauricus Buturlin, 1904. From Crimea and E of Dnieper River eastwards around coast of Black Sea to W Asia Minor, though not in uplands where replaced by purpurascens.

- Like nominate, but decidedly long-winged. Gloss of head green, of body bronze-purple, of flanks and upper wing-coverts greenish bronze. Underwing blackish with pale fringes of coverts. Nearly spotless in breeding plumage.

- Sturnus vulgaris purpurascens Gould, 1868. E Turkey to Tbilisi and Lake Sevan, in uplands on E shore of Black sea replacing tauricus.

- Like nominate, but wing longer and green gloss restricted to ear-coverts, neck and upper chest. Purple gloss elsewehere except on flanks and upper wing-coverts where more bronzy. Dark underwing with slim white fringes to coverts.

- Sturnus vulgaris caucasicus Lorenz, 1887. Volga Delta through eastern Caucasus and adjacent areas.

- Green gloss on head and back, purple gloss on neck and belly, more bluish on upper wing-coverts. Underwing like purpurascens.

- Sturnus vulgaris porphyronotus (Sharpe, 1888). Western Central Asia, grading into poltaratskyi between Dzungarian Alatau and Altai.

- Very similar to tauricus but smaller and completely allopatric, being separated by purpurascens, caucasicus and nobilior.

- Sturnus vulgaris nobilior (Hume, 1879). Afghanistan, SE Turkmenistan and adjacent Uzbekistan to E Iran.

- Like purpurascens but smaller and wing shorter; ear-coverts glossed purple, and underside and upperwing gloss quite reddish.

- Small; purple gloss restricted to neck area and sometimes flanks to tail-coverts, otherwise glossed green.

- Sturnus vulgaris minor (Hume, 1873). Sind Starling. Pakistan.

- Small; green gloss restricted to head and lower belly and back, otherwise glossed purple.

Several other forms have been named, but are generally no longer considered valid. Most are intergrades from where the ranges of various subspecies meet.[5]

- S. v. ruthenus Menzbier, 1891 and S. v. jitkowi Buturlin, 1904 are intergrades between vulgaris and poltaratskyi from western Russia.

- S. v. graecus Tschusi, 1905 and S. v. balcanicus Buturlin and Harms, 1909 are intergrades between vulgaris and tauricus from the southern Balkans to central Ukraine (where there is some intergradation with poltaratskyi too) and throughout Greece to the Bosporus.

- S. v. heinrichi Stresemann, 1928 is an intergrade between caucasicus and nobilior in northern Iran.

- S. v. persepolis Ticehurst, 1928 from southern Iran (Fars Province) is very similar to vulgaris; it is not clear whether it is a distinct resident population of simply migrants from southeastern Europe.

Description

It is among the most familiar of birds in temperate regions. It is 19–22 cm long, with a wingspan of 37–42 cm and a weight of 60–90 g. The plumage is shiny black, glossed purple or green, and spangled with white, particularly strongly so in winter. Adult male European Starlings are less spotted below than adult females. The throat feathers are long and loose, and used as a signal in display. Juveniles are grey-brown, and by their first winter resemble adults though often retain some brown juvenile feathering especially on the head in the early part of the winter. The legs are stout, pinkish-red. The bill is narrow conical with a sharp tip; in summer, it is yellow in females, and yellow with a blue-grey base in males, while in winter, and in juveniles, it is black in both sexes. Moulting occurs once a year, in late summer after the breeding season is finished; the fresh feathers are prominently tipped white (breast feathers) or buff (wing and back feathers). The reduction in the spotting in the breeding season is achieved by the white feather tips largely wearing off. Starlings walk rather than hop. Their flight is quite strong and direct; they look triangular-winged and short-tailed in flight.[3][4]

Confusion with other species is only likely in Iberia, the western Mediterranean and northwest Africa in winter, when it has to be distinguished from the closely related Spotless Starling, which, as its name implies, has less spotting on its plumage. The Spotless Starling can also be diagnostically distinguished at close range by its longer throat feathers.[4] At a more basic level, adult male European Blackbirds can easily be distinguished by more slender body shape, longer tail, and behaviour; they hop instead of walking and do not probe for food with open bills. In flight, only the much paler waxwings share a similar flight profile.

Voice

The Common Starling is a noisy bird uttering a wide variety of both melodic and mechanical-sounding sounds, including a distinctive "wolf-whistle". Starlings are mimics, like many of its family. In captivity, Starlings will learn to imitate all types of sounds and speech earning them the nickname "poor-man's Myna".

Songs are more commonly sung by males, although females also sing. Songs consist of a mixture of mimicry, clicks, wheezes, chattering, whistles, rattles, and piping notes.[7] Besides song, 11 other calls have been described, including a Flock Call, Threat Call, Attack Call, Snarl Call, and Copulation Call.[7] Birds chatter while roosting and bathing—making a great deal of noise that can frustrate local human inhabitants. Even when a flock of starlings is completely silent, the synchronized movements of the flock make a distinctive whooshing sound that can be heard hundreds of meters.[7]

Distribution and habitat

European Starlings prefer urban or suburban areas where artificial structures and trees provide adequate nesting and roosting sites. They also commonly reside in grassy areas where foraging is easy—such as farmland, grazing pastures, playing fields, golf courses, and airfields.[8] They occasionally inhabit open forests and woodlands and more rarely in shrublands such as the Australian heathland. European Starlings rarely inhabit dense, wet forests (i.e. rainforests or wet sclerophyll forests). Common starlings have also adapted to coastal areas, where they nest and roost on cliffs and forage amongst seaweed. Their ability to adapt to a large variety of habitats has allowed for their dispersal and establishment throughout the world—resulting in a habitat range from coastal wetlands to alpine forests, from sea level to 1900 meters above sea level.[8]

Widespread throughout the northern hemisphere, the European Starling is native to Eurasia and is found throughout Europe, northern Africa (from Morocco to Egypt), northern India, Nepal, the Middle East (including Syria, Iraq, and Iraq), and north-western China. Furthermore, it has been introduced to and successfully established itself in New Zealand, Australia, North America, Fiji, and several Caribbean islands. As a result, it has also been able to migrate to Thailand, Southeast Asia, and New Guinea.[9] In Australia, European Starlings are referred to as the Common Starling, and are present throughout the southeast, although some isolated populations have been observed in northern and Western Australia. They are prevalent throughout New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania, and scattered sites in the southeastern part of Western Australia.[10]

Behaviour

It is a highly gregarious species in autumn and winter. Flock size is highly variable, with huge flocks providing a spectacular sight and sound usually occurring near roosts. These huge flocks often attract birds of prey such as Merlins or Sparrowhawks. Flocks form a tight sphere-like formation in flight, frequently expanding and contracting and changing shape, seemingly without any sort of leader. Very large roosts, exceptionally up to 1.5 million birds, can form in city centres, woodlands, or reedbeds, causing problems with their droppings. These may accumulate up to 30 cm deep, killing trees by their chemical concentration; in smaller amounts, the droppings are, however, beneficial as a fertiliser, and therefore woodland managers may try to move roosts from one area of a wood to another to spread the benefit and avoid large toxic deposits.[11]

Huge flocks of more than a million Starlings are observed just before sunset in spring in southwestern Jutland, Denmark. There they gather in March until northern Scandinavian birds leave for their breeding ranges by mid-April. Their flocking creates complex shapes against the sky, a phenomenon known locally as sort sol ("Black Sun"). To witness this spectacle, the best place are the seaward marshlands (marsken in Danish) of Tønder and Esbjerg municipalities between Tønder and Ribe.[12]

Flocks of anything from five to fifty thousand Starlings form in areas of the UK just before sundown during mid winter. These flocks are commonly called a Starling "Moot".

Starlings are hunted by birds of prey, including the Peregrine Falcon and Brown Falcon. However, in the 1970s the consumption of chemically treated (DDT) crops by the starlings which were subsequently eaten by Peregrine Falcons caused a dangerous build-up of the toxin in the falcon. As a result, lower reproductive success was observed as a result of thinner eggshells and a build-up of organochlorine residues in eggs.[13]

European Starling nests are especially vulnerable to predators such as stoats, foxes, and humans. Common Mynas are also a threat, as they often evict eggs, nestlings, and adult starlings from their nests.[14]

Feeding

The European Starling is insectivorous, and typically consumes insects including caterpillars, moths, and cicadas, as well as spiders. While the consumption of invertebrates is necessary for successful breeding, starlings are omnivorous and can also eat grains, seeds, fruits, nectars, and garbage, if the opportunity arises.[15][16][17] There are several methods by which they forage for their food; but for the most part, they forage from or near the ground, taking insects from or beneath the surface of the soil. Generally, starlings prefer foraging amongst short-cropped grasses and are often found between and on top of grazing animals out to pasture.[17] Large flocks forage together, in a practice called “roller-feeding”: where the birds at the back of the flock continually fly to the front of the flock as they forage so that every bird has a turn to lead (1957).[18] The larger the flock, the nearer individuals are to one another while foraging. Flocks often forage in one place for some time, and return to previous successfully foraged sites.[18] There are four types of foraging observed in the European Starling:[18]

- Probing: The bird plunges its beak into the ground randomly and repetitively until an insect has been found. Probing is often accompanied by bill gaping (‘zirkelning’) where the bird opens its beak while probing to enlarge a dirt hole or to separate a lump of grass. This instinctual behavior has been observed in starlings eating garbage from plastic garbage bags—the bill gaping results in the opening of holes in the garbage bags that allow for extrication of consumables.

- Sallying: When the starling grabs an invertebrate directly from the air, a particularly successful behavior among this species.

- Lunging: A less common technique where the starling lunges forward to catch a moving target or invertebrate on the surface floor.

- Gleaning: When the bird pulls backwards to extricate an earthworm from the soil.

Among European Starling, sallying and probing are the most common foraging behaviors.

Courtship

Unpaired males begin to build nests in order to attract single females. Males often decorate the nest with ornaments (such as flowers) and fresh green material which the female later disassembles upon accepting him as a mate .[19][20] The males sing throughout much of the construction and even more so when a female approaches his nest. Following copulation, the male and female continue to build the nest. Common nesting locations include inside hollowed trees, buildings, tree stumps, and man-made nest-boxes. Nests are typically made out of straw, dry grass, twigs and inner lining made up of feathers, wool, and soft leaves. Construction typically takes 4 to 5 days and may continue through incubation.[21] Fresh herbs are added to nests and work as insect repellent.[19][22]

Starlings are both monogamous and polygamous, although broods are generally brought up by one male and one female, occasionally the pair may have an extra helper. Pairs may be part of a larger colony, in which case several other nests may occupy the same or nearby trees.[7]

Breeding

The breeding season begins in early spring and summer. In Australia, eggs are typically laid from late September to late November but the range extends from late July to December.[7] Following copulation, female European Starlings will lay an egg on a daily basis over a period of several days. If an egg is lost during this time period, she will lay another egg to replace it. The eggs (4-5) are small elliptical blue (and occasionally white) eggs that commonly have a glossy appearance to them.[21] Incubation lasts 13 days, although the last egg laid may take 24 hours longer than the first to hatch. Both parents share the responsibility of sitting on top of the eggs. However, the female spend more time incubating the eggs than the male, and is the only parent to do so at night (while the male returns to the communal roost).[23] The young are born blind and naked. They develop light fluffy down within 7 days of hatching and sight within 9 days. Nestlings remain in the nest for 3 weeks, where they are fed continuously by both their parents. Fledglings continue to be fed by their parents for 1–2 weeks. Pairs can raise up to three broods per breeding season, frequently reusing and relining the same nest.[23] Within two months, most juveniles have molted and gained their first basic plumage. Juveniles acquire their adult plumage the following year.[14]

Intraspecific brood parasites are common in European Starling nests. Female "floaters" (unpaired females during the breeding season) present in colonies often lay eggs in another pair's nest.[24] Additionally, fledglings have been reported to invade their previous nests or neighboring nests and evicting the new brood.[23]

Relationship with humans

Status and conservation

Overall, the European Starling is listed by the IUCN as being a species of least concern.[25] However, it has been adversely affected in northern Europe by intensive agriculture, and in several countries, it has been red-listed due to declines of more than 50%. In the United Kingdom, it declined by more than 80% between 1966 and 2004; although populations in some areas—such as Northern Ireland—are stable or even increasing, those in other areas—mainly in England—declined even more sharply. The overall decline has been attributed to a loss of food-rich permanent pasture, leading to the low survival rates of young birds.[26] Major declines have also been observed from 1980 onward in Sweden, Finland, northern Russia (Karelia), and the Baltic States, and smaller declines in much of the rest of northern and central Europe.[3] In contrast, there have been increases in southern Europe, particularly in Italy, southern France, and northeastern Spain where the species first began breeding in the 1960s.[3]

Earlier, the European Starling had shown marked increases throughout Europe in the period 1800-1900. Before 1800, it had a disjunct range in the British Isles, absent from central and southern Scotland, with S. vulgaris zetlandicus in the far north and northwest (Shetland, Orkney, Caithness, Outer Hebrides), and S. vulgaris vulgaris south of the Scottish-English border; it was also rare or regionally absent in Ireland, western Wales and western and northernmost England. Between 1800 and 1900, S. vulgaris vulgaris colonised north and westward from England to Ireland and all of Scotland except for Shetland (where zetlandicus remains present); since 1935, this subspecies has also spread to Iceland, where it now breeds in the southeast and southwest.[3][27] S. vulgaris vulgaris is also occasionally seen in the Faroes.

Introduced populations

This adaptable species is considered to be a pest in several of the countries to which it has been introduced. The European Starling is a hole-nesting species and will nest in just about any cavity it finds. It has affected native species where it has been introduced because of competition for nest sites. For example, in North America, the Purple Martin is now widely dependent on artificial nest houses put up by humans, which must be protected from colonization by European Starlings.

Australia

The Common Starling was originally introduced to Australia in order to decrease the population of crop pests—insects which the starlings were known to eat. Early settlers looked forward to the bird’s arrival believing that starlings were also important to the pollination of flax, an important crop. Nest-boxes for the newly released species were placed on farms and near crops.[28] The Common Starling was introduced to Melbourne in 1857 then Sydney in 1880.[29] By the 1880s, established populations were present in the southeast thanks to the work of acclimatization committees.[30] By the 1920s, starlings were widespread through Victoria, Queensland, and New South Wales, but, they were now recognized as pests and Western Australia banned their import in 1895.[29][30]

The Common Starling threatens both Australian economy and biodiversity. They commonly eat and damage fruit from orchards, such as grapes, peaches, olives, currants, and tomatoes. In addition, starlings dig up newly sown grain and diminish already growing crops—an easy task for a flock of 500 – 150,000 birds.[17] The Common Starling will also eat and foul food meant for livestock, putting the health of livestock at stake. The accumulation of waste left behind by large flocks may ruin human water supplies and cities, as well as natural habitats for Australian fauna.[17]

Australia is home to numerous endemic plants and animals — species that live nowhere else on earth. The Common Starling is an aggressive bird that displaces other hollow nesting, endemic Australian birds.[31] With so many of these native species already endangered, the starling poses a significant threat. They also pose a risk to the native and endemic Australian flora. Seeds will often germinate more successfully after ingestion, and, as they are capable of eating almost any kind of seed and flying great distances, Common Starlings are excellent weed dispersers. They are responsible for spreading invasive plant species such as the Bridal Creeper.[32]

As a result, the government of Western Australia has gone to great lengths to keep the Common Starling on the other side of their borders. In the state's 2007-2008 budget, an additional $AUD 4.9 million (2007) was allocated to the control and eradication program.[32][33] New flocks are routinely shot down, while the less cautious juveniles are trapped and netted.[30] New methods are currently being developed, the first of which tags one bird and follows it back to the rest of the flock, exposing a new population for termination.[34] The second analyzes the DNA of Australian Common Starling populations to track where the migration from eastern to Western Australia is occurring so that better preventative strategies can be used.[35]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the Starling was introduced in 1862, and now occurs in most of the country.

North America

Although there are approximately 200 million starlings in North America, they are all descendants of approximately 60 birds (or 100 [1]) released in 1890 in Central Park, New York, by Eugene Schieffelin, who was a member of the Acclimation Society of North America reputedly trying to introduce to North America every bird species mentioned in the works of William Shakespeare.[36]

As an introduced species, European Starlings are not protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.[37] Starlings are considered a nuisance species in North America. The birds, which travel in enormous flocks, often pose dangers to air travel, disrupt cattle operations, chase off native birds, and roost on city blocks. They leave behind corrosive droppings and hundreds of millions of dollars of damage every year. In 2008, U.S. government agents poisoned, shot and trapped 1.7 million starlings, more than any other nuisance species.[38]

South Africa

In South Africa, the Starling was introduced in 1890, and is now common in the southern Cape region, and less common north to the Johannesburg area.[39]

Cultural references

- In Welsh Mythology Branwen tamed a starling and sent it across the Irish Sea with a message to her brother Bran, who sailed from Wales to Ireland to rescue her with his brother, Manawydan.

- The starling's ability to mimic human speech earned the bird this cameo in William Shakespeare's Henry IV:

- The king forbade my tongue to speak of Mortimer. But I will find him when he is asleep, and in his ear I'll holler 'Mortimer!' Nay I'll have a starling shall be taught to speak nothing but Mortimer, and give it to him to keep his anger still in motion.

- William Butler Yeats poem "The Stare's Nest by My Window" is about a starling's nest. "Stare" is a local, informal variation of "starling."

- On their 1999 album "Brighten the Corners, the '90's indie rock band Pavement released the song Starlings of the Slipstream.[2] The band was from California (specifically, the northern-most part of the San Joaquin Valley region), where European Starlings are ubiquitous [3].

- One of the main characters of the novel and film The Silence of the Lambs is named Clarice Starling. At one point, another character makes a pun based on her name and tells her to "Fly away, little Starling... Fly, fly, fly..."

- In the Nintendo DS video games, Pokémon Diamond, Pearl and Platinum the Pokémon species Starly and its "Evolutions" are based upon the common starling.

References

- ↑ Feare, Chris; Craig, Adrian (1998). Starlings and Mynas. Christopher Helm. pp. 21,29, 186–187. ISBN 0-7136-3961-X.

- ↑ Zuccon, D., Cibois, A., Pasquet, E., & Ericson, P. G. P. (2006). Nuclear and mitochondrial sequence data reveal the major lineages of starlings, mynas and related taxa. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41 (2): 333-344. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.007 (HTML abstract)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Snow, D. W. & Perrins, C. M. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic Concise Edition. OUP ISBN 0-19-854099-X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Svensson, L. (1992). Identification Guide to European Passerines. Stockholm ISBN 91-630-1118-2.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Vaurie, C. (1954). Systematic Notes on Palearctic Birds. No. 12. Muscicapinae, Hirundinidae, and Sturnidae. Amer. Mus. Novit. 1694: 1-18

- ↑ Snow, D. W., Perrins, C. M., Doherty, P., & Cramp, S. (1998). The complete birds of the western Palaearctic on CD-ROM. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192685791.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Higgins, P.J., Peter, J.M., & Cowling, S.J. (Eds) 2006, Handbook of Australian, New Zealand, and Antarctic Birds. Volumes 7: Boatbill to Starlings. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, p. 1924.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Higgins et al., p. 1907

- ↑ Higgins et al., p. 1908

- ↑ Higgins et al., pp. 1908-9

- ↑ Currie, F. A., Elgy, D., & Petty, S. J. (1977). Starling Roost Dispersal from Woodlands. Forestry Commission Leaflet 69. ISBN 0-11-710218-0.

- ↑ "Black Sun in Denmark". Earth Science Picture of the Day. 2006-06-19. http://epod.usra.edu/archive/epodviewer.php3?oid=309856. Retrieved 2006-10-07.

- ↑ Pruett-Jones, S., White, C. & Emison, W. 1980, "Eggshell thinning and organochlorine residues in eggs and prey of Peregrine Falcons from Victoria, Australia", EMU, vol. 80, no. 5, pp. 281-287.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Higgins et al., p. 1928

- ↑ Thomas, H.F. 1957, The Starling in the Sunraysia District, Victoria. Part I. Emu 57, 31–48.

- ↑ Higgins et al., p. 1913

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Kirkpatrick, W. & Woolnough, A.P. 2007, "Common Starling", Pestnote, Department of Agriculture and Food Australia.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Higgins et al., p. 1914

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Brouwer, L. & Komdeur, J. 2004, "Green nesting material has a function in mate attraction in the European starling", Animal Behaviour, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 539-548.

- ↑ Higgins et al., p. 1923

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Higgins et al., p. 1926

- ↑ Gwinner, H. & Berger, S. 2008, "Starling males select green nest material by olfaction using experience-independent and experience-dependent cues", Animal Behaviour, vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 971-976.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Higgins et al., p. 1927

- ↑ Sandell, M.I. & Diemer, M. 1999, "Intraspecific brood parasitism: a strategy for floating females in the European starling", Animal Behaviour, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 197-202.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2004). Sturnus vulgaris. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 6 May 2006. Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- ↑ British Trust for Ornithology: Starling

- ↑ Holloway, S. (1996). The Historical Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland: 1875–1900. T & A D Poyser ISBN 0-85661-094-1.

- ↑ Higgins et al., pp. 1911-2

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Higgins et al., p. 1910

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Woolnough, A. P., Massam, M. C., Payne, R. L., and Pickles, G. S. 2005, "Out on the border: keeping starlings out of Western Australia. In ‘Proceedings of the 13th Australasian Vertebrate Pest Conference’", pp. 183–189. (Wellington, New Zealand.)

- ↑ Pell, A.S. & Tidemann, C.R. 1997, "The impact of two exotic hollow-nesting birds on two native parrots in savannah and woodland in eastern Australia", Biological Conservation, vol. 79, no. 2-3, pp. 145-153.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 World Wildlife Fund (Australia). Starlings, a threat to Australia's unique ecosystems (pdf file).

- ↑ Government of Western Australia, Government Media Office}} (2007): Ministerial Press Release, 11 May 2007: New funding to control European starlings. Retrieved 2007-MAY-11.

- ↑ Woolnough, A.P., Lowe, T.J., and Rose, K. 2006, "Can the Judas technique be applied to pest birds?", Wildlife Research 33, 449–455.

- ↑ Rollins, L.A., Woolnough, A.P., and Sherwin, W.B. 2006, "Population genetic tools for pest management: a review", Wildlife Research 33, 251–261.

- ↑ "Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology species account for European Starling". http://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/BirdGuide/European_Starling.html.

- ↑ "U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service: Birds protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act". http://www.fws.gov/migratorybirds/intrnltr/mbta/taxolst.html. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Stark, Mike (2009 Shock and caw: Pesky starlings still overwhelm Yahoo News. Accessed 6 September 2009

- ↑ SASOL Bird e-guide: Common Starling

External links

- Florida's Introduced Birds: European Starling ("Sturnus vulgaris") - University of Florida fact sheet

- ARKive - images and movies of the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

- RSPB

- BBC

- Cornell University

- BBC dawn chorus Sample of the starling's song

- European Starling videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta